The living owe it to those who no longer can speak to tell their story for them.

—Czesław Miłosz

I got off the bus into the early dark. That particular November dusk already filled with a cool sensation. A woman stood still beneath the amber streetlight. Leaves from the trees that lined the street dropped and brushed past her hair and shoulders. They had clung to their branches until with a quiet resolve, they finally let go – drifting past her before resting on the ground softly, waiting for the wind to carry them somewhere. She looked at me as if we had agreed to meet and I hadn’t remembered.

“Would you come with me?” she beckoned in a tone so soft that I could hardly hear it.

As if under a spell, I heard myself say yes and followed her. At the time, I didn’t know why there was none of the usual calculations and hesitations that rise when a stranger asks too much too quickly. I could hear only my footsteps as the leaves crackled under them. Perhaps I was too conscious of my own.

She led me farther from the bus stop, away from the constellation of neon lights on Shaukiwan Road. We continued until the city’s bluster and din faded behind us. Before I knew it, we were walking past a row of dimly lit Hong Kong cafés, their neon signs flickering in the humid air. Through fogged windows, I glimpsed marble tables, red vinyl stools, and ceiling fans turning lazily above the haze of cigarette smoke. From an old radio came the ghostly strains of Cantonese opera—music from another time. The aura was eerily familiar. It felt as though we had stepped into the Hong Kong of my childhood.

As we turned into a narrow alley, an old worn building surfaced from the dark, its concrete the colour of weak tea; balconies rusted, laundry lines hanging slack. I recognized the type immediately—a post-war tenement like the one I’d grown up in, the kind still sheltering families in some run-down areas today. But this one stood strangely isolated, a solitary block with no neighbours, as if the city had receded around it like a tide. She looked up at a single window that framed a faint yellow light.

“So… it’s your home?” I asked, needing something – anything – to fill the silence between us.

“I keep a place,” she said. “It keeps me.”

That’s where I … she paused before she uttered ‘live’, looking up at that lit window. In the immensity of the dark, there was no mistaking it; every other unit was a blind eye.

The entrance to the mansion smelled musty with a hint of rust. No bulb burned. I felt my way up a wooden spiral. The banister was worn smooth with the polish of hands that, as I would later find out, had long stopped coming home. I was about to turn my phone light on as I was ascending. But she stopped me. Please don’t , her voice slightly trembled . The staircase was too narrow to permit us to walk abreast. I followed her, with each stair groaning under my weight. I was curious though why hers were accepted with its stoical silence .

At the top, her hand hovered near the latch of an rusty iron gate. It’s a bit nippy inside, she warned.

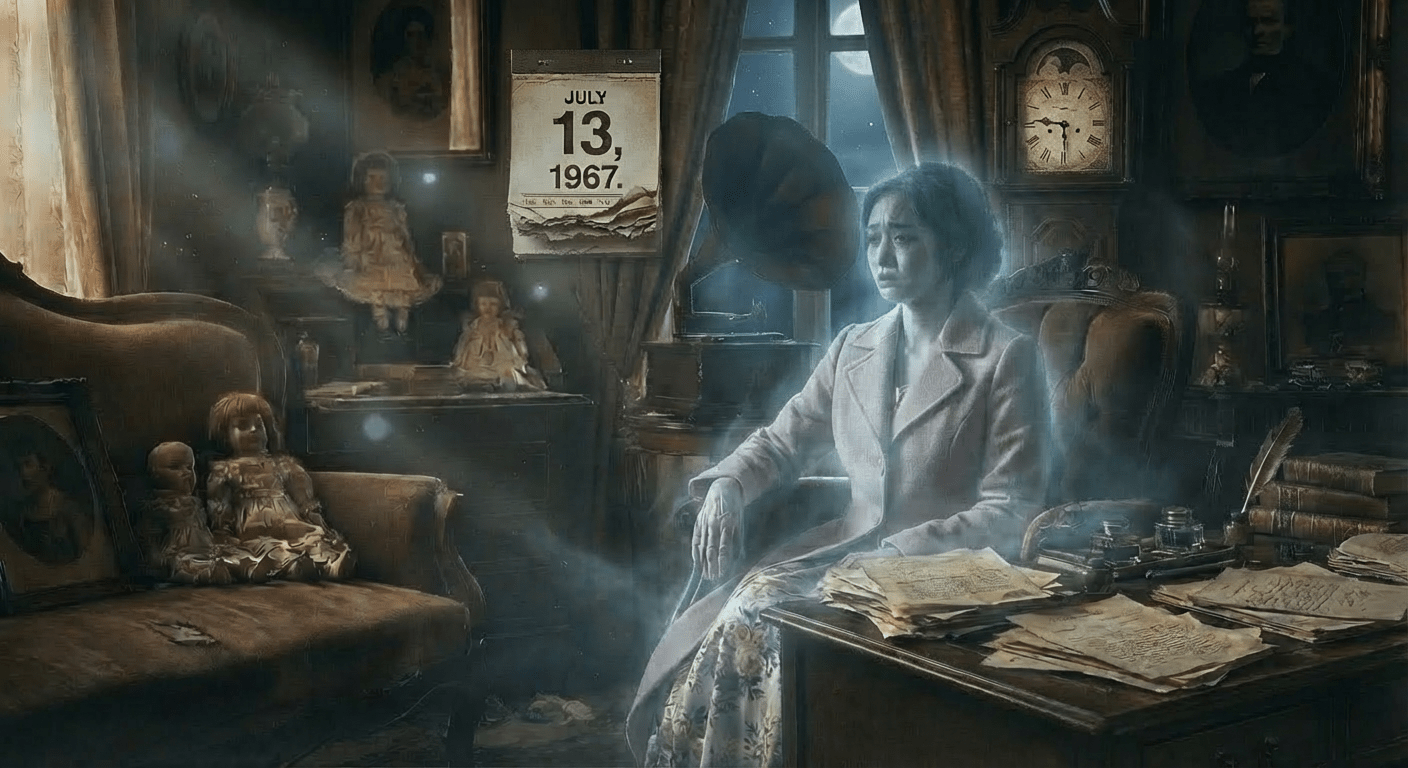

The door creaked open. A small dining room awaited inside, lit by a weak bulb that struggled against the darkness. I could see her more clearly now. She looked in her early twenties—her complexion pale, her eyes touched with sorrow. She was so pale she might have been formed from the weak light itself. She was wearing a pink coat over a floral, knee-length skirt, the kind of style my mother and her contemporaries would wear in her young days. Most of the time, she gazed towards the window, as if searching for something far beyond it.

I wonder how the world outside is now, she mused.

You may well step out and feel it yourself, I was going to say. But I held back, surmising that she looked so sickly that she must have been too frail to go outside. Yes, it’s a bit chilly outside. I said. I knew I’d said something irrelevant. She pressed herself against the window for sometime. She then left her face off the window. The window did not leave any steam as if she was holding her breath while she was looking.

Your dress, I said, looking at the careful pleats and the modest hem. It looks belonging to another era.

Really? She glanced at the mirror as if noticing it for the first time in years.

No one dresses like that anymore, I said gently.

I suppose fashions change. How long has it been? She smoothed the fabric with pale fingers.

She turned her eyes to the wall above the table.

A photograph in a rosewood frame hangs on the wall. It captures a young woman in her early twenties. She stands in a park, framed by a profusion of flowers, her hands loosely folded as she smiles toward something beyond the camera’s view. Her image, in her pink dress and light windbreaker, create a relief against the surrounding azaleas, lending balance to the composition. The sunlight falls across her right cheek, forming a small, luminous highlight that draws attention to her calm, youthful face. Her unblemished complexion and bright clear eyes exude a freshness that unmistakably only belongs to the very young. Perhaps because there is a breeze stirring her hair, sending soft waves across her shoulders, she gently restrains with her hand a few strands from drifting free. Her body leans lightly against the trunk of a nearby tree, giving the pose an easy, unforced grace. Her smile captures a quiet, fleeting moment of natural warmth.

I took this in the Botanical Garden in the autumn of 1966, she touched the photograph. I sensed an uncanny moment as I looked between the image and the woman beside me. They were the same. Not similar, not resembling, but the same. The same pink coat, the same angle of the shoulders, the same tilt to her chin—only much paler now, perhaps the years had slowly drained the colour from her while leaving everything else untouched. It was as though she’d stepped out of that silver halide a moment ago and spent decades trying to find her way back into the frame.

The room suddenly felt unmoored from reality. Where was I? More importantly—who was it that was sitting across from me? The girl from the photograph who never ages past that distant autumn of 1966, or something that had simply borrowed her shape and refused to let it change?

Are you afraid of me? Perhaps she had noticed that I was shivering. Yet the profound sorrow in her face stirred something gentler in me, softening my fear before it could take hold.

No, not really. I composed myself.

As she moved towards the window, I took the moment to survey the place. It had the stillness of a held breath. Navy blue paint peeled from the walls in long strips, exposing patches of gray plaster underneath. On the dresser, an old wind-up clock sat silent, its key still protruding from the back, hands frozen at some forgotten hour. A lamp with a yellowed shade cast dim light over a small table which held its arrangement like a museum display —a teacup with dried residue forming rings inside, a pair of glasses folded over a newspaper, a bowl with three wrapped coconut sweets, all coated with a thin film of dust.

You want to…. tell me a story? I asked, trying to establish why she wanted me to come with her.

If I doubted anything about reality, it’s never that reality had deserted us. This WAS reality now: The flat. The woman. The clock. The table and its things. Actually, everything within these walls. This was what was real—so why should I trouble myself with my own idea of it? I’d completely lost track of what that “reality” was supposed to be anyway. Whatever order of reality this was, it had become the only one that mattered. And I, through my deepening entanglement with this place, felt myself becoming part of the reality the flat contained—as if this was where I’d always been meant to be.

I was no longer afraid.

On the wall, a calendar showed the 13th of July 1967.

The calendar has held that date for as long as anyone remembers, she said. it hasn’t been turned ever since .

I didn’t die here, she added.

Where then? I asked, confused.

Her eyes moved to the window. The sash was painted shut, sealed by decades of humidity and neglect. That window hasn’t opened since the 13th July . I walked to Sai Wan Ho Jetty on that day. There’s a small stretch of water there, away from the main harbour traffic. That’s where I went in. Her voice was matter-of-fact, as if describing a routine errand. But afterwards, I found myself back here. This was my home. Her gaze drew mine back to the calender. Everything about me ended and began all in the same day.

A silence fell between us. My gaze drifted around the unchanged room and caught on something I hadn’t noticed before—a clothesline stretched from wall to wall. A single floral shirt hung there, arms spread slightly as if mid-gesture, the fabric holding the ghost of a shape. The print had faded but I could still make out small blue flowers against what was once white.

She followed my gaze. I wore that on my last day.

By this time, I already felt at ease with her and felt at home to ask more. She sat down at the table, running her fingers along its worn edge.

People say I died for love, she said. It makes the story simple. It fits neatly into their desire of hearing a tragic romance. She looked at me. But it wasn’t just him. It was everything the waiting turned me into.

She told me about how she fell in love with a young man. He promised he would come back from his study overseas, —perhaps in one year, he said. At first the letters came thick and eager. Then they thinned, like a season fading. Then nothing. Hers went out into the void.

His name doesn’t matter anymore, she said. What happened to me was bigger than a name.

I had a life of my own to live. Her tone grew more certain as she continued. I taught primary school to save money to go to a university abroad. I had to tend to my aging mother and look after my little brother. I waited for my opportunity. I waited for his return. Over the years, that life turned out to be one of waiting, hoping and eventually disenchantment. The waiting was just one thread woven through all the rest.

The things on the table chimed in with their testimony. A rejection letter from the University of London, —the paper yellowed at the edges but the words still sharp. Two tickets for West Side Story, the show date two months past, never used. A stack of pupils’ exercises she’d been marking, red pen still uncapped beside them. An unfinished lesson plan for teaching the alphabet, the letters A through M carefully illustrated; the rest left forever waiting. Amidst all this lay a scrap of notepad paper on which was written in a steady and careful hand: prepare pills for mother.

Every day was full. She continued: But full of things that led nowhere. I was always preparing for a life that kept being postponed.

I spent my life waiting. At first, I knew what I was waiting for: His return, the day when I could have saved enough money for university, the results of applications. And then year after year, I lost focus. It all blurred into a dull sensation, waiting with no specific goal. It just became a dreary game of waiting, yet I felt compelled to wait. As for waiting for what, I was no longer sure. She looked away, her voice fading.

Instead of letters coming from him, rumours found her. Some said he had fallen ill. Some said he had stayed overseas, married there. Someone swore they saw him back in the city, thinner, changed, a quick shadow near the tram stop.

I waited for years, she murmured. When footsteps came down the corridor, my heart quickened. Could it be him? But the doorbell never rang with that particular visitor she had been expecting —a slim young man with hair parted to the right, who would say her name and pull her into his embrace.

She paused, then again: Waiting became the role everyone gave me. At first, I told myself stories— He’ll come back soon, I’d whisper to my reflection. Just save a bit more money, then apply to university again. But my mother had other plans. You must wait until your brother grows up, she would say. A daughter’s duty is to family, not books. So I waited for my brother to finish school. Waited for enough savings. Waited for life to somehow rearrange itself into what I wanted it to be. Each year, another reason to postpone. Another obligation. And he—the one who never wrote, never returned— became just one more thing in a long list of things that would never come.

By the time I finally understood he wasn’t coming back, it didn’t matter anymore. The role had already been written for me. One word: Wait. Then there was another voice inside me gathering momentum: Sylvia, you can break it. Now, I know what I should do. She said calmly, and I could hear in her voice that fatal moment of clarity—when the path forward had suddenly revealed itself.

I didn’t die for a man, she said firmly. I refused the life that made waiting my whole identity.

She told me about her childhood—growing up in a modest family where her younger brother always came first, no matter what she achieved. Her father didn’t particularly like working; responsibilities slid off him and onto everyone else. But she cherished small joys too: a stray cat that chose their doorstep, the triumph when her first loaf of bread rose properly in the oven. And that first Christmas ball at school when she was 16—she wore a blue floral dress and when a boy asked her to dance, she felt something shift inside her, some door opening onto a different possible life.

Those were the little stories, she said, the threads in the fabric. But they felt like sparks—bright for a breath, then gone into the dark.

She had been keeping diaries —years of them—and a bundle of the man’s letters. I threw them away. They all contained an agonising voice of a life that clamour for fulfillment yet being dragged by indefinite waiting. When I decided to define my life on my own terms, I let them go. Each entry pinned me to a day I didn’t want to live in anymore. When I burned them , I felt a tremendous sense of letting go, symbolic if not actual.

I asked if that brief liberation might have prepared her for what was to come.

Sort of, she said softly. I still felt crushed by the gravity of the present. The diaries were the first refusal. Death was the only thing left that I could choose .

On the 13th of July, the feeling that had been humming for years gathered itself. Everything she had postponed stood around her at once, and all the doors she’d been promised were still shut. It was as if a black circle opened in the middle of the room, made from every “not yet” she had ever obeyed.

It wasn’t a rushed decision, she said. I stepped into it – she stressed the word – refusing to keep orbiting a life that never let me begin.

I missed my chances, she whispered, and a tear rolled down her cheek. I was cut off in my prime. I lost the chance to find out what living feels like over a long stretch. Maybe even to learn what a love that lasts actually is.

Maybe, I said. You might have suffered more by living. Or less. But who knows? We only guess what other lives could have been for us.

She smiled. You’re saying there might have been lives I saved myself from without knowing?

I’m saying none of us gets the full accounting. Most lives are patchwork anyway, and whatever warmth we find comes from the stitching itself, from creating meaning for your present.

She was silent again. But I had tried, she said.

She glanced at the calendar. And this? What do you call this?

A life with one day kept, I said. Not wasted— just a different way of becoming. You spent everything you had to preserve that single moment, that exact point you ended your life.

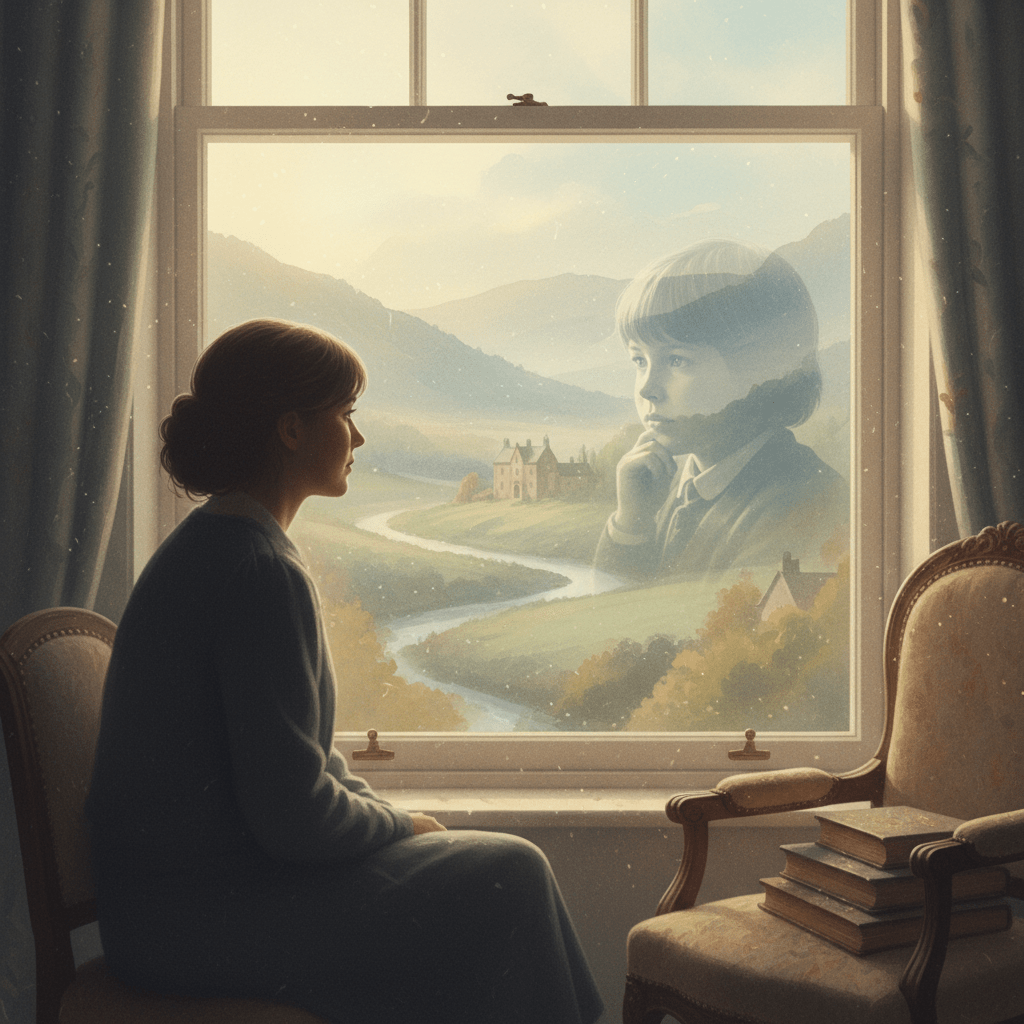

She was quiet for a moment. I missed the chance to grow old. To watch those pupils become adults with their own pupils to mark. And to see if the city would change or if I would.

Perhaps by freezing yourself that day, it’s not so much the dramatic moments you would have missed as… that gentle erosion and shaping that comes from everyday life. Like an artist’s kneading, you know? Small things—hair going gray, hands that know their work, that favourite teacup that gets worn smooth where your thumb rests. The window where you’d watch the same trees turn green, then brown, year after year. Everything in between.

Yes. And more, she said. I missed the chance to forgive, she continued with the words coming harder now. To forgive him for not returning. To forgive myself for waiting. Maybe forgiveness only comes with time, and I didn’t give myself enough.

Do you regret it? I asked.

The question seemed to fill the room. She didn’t answer. The silence stretched until it became its own reply: some choices are beyond regret. They simply are what happened, the path the story took.

Why tell me all this? I asked.

I need someone to know I existed—that our love was real, even if it ended in shadow. That I once lived with a throbbing heart. Please write that I did not succumb to frustration. Write that I refused to live by the script life handed me. I didn’t accept the part.

She looked at me directly. Write that my story isn’t that of Ophelia floating downstream with her flowers. I chose to leave—I just never got all the way gone.

Never got all the way gone? I echoed, not quite understanding.

I’m caught, she said, her voice steady but distant. Too far from life to return, not far enough gone to reach whatever comes after. Suspended in the space between my memory and the next world’s threshold—like a door that won’t quite close. Her words made me think of the Haunted Mansion’s ballroom scene in Disneyland—spirits locked in an endless waltz, circling through dusty air and faded music. Like her, they were caught in a single moment stretched into forever, performing the same steps in the half-light between worlds.

People like to box me into a neat romance that failed—a pretty tragedy with a moral attached. But I’m not a cautionary tale. I was a person.

So you’ll write my story? She looked at me, almost beggingly.

Her expectations weighed on me like a coat I hadn’t asked to wear but couldn’t refuse. This was no longer just about a young woman long forgotten by history. Her story had become something else to me now—a debt between the living and the dead, a responsibility I hadn’t sought but recognized. Perhaps it was the way she’d walked me through those collapsed decades, showing me how thin the membrane was between her 1967 and my present 2025. Or perhaps it was simpler: she had no one else to ask, and I was the only one who’d followed her up those stairs, the only one who’d sat in her unchanged apartment and conversed with her – though anyone reading this may think it mere imagination.

And perhaps most importantly —though I can’t quite explain it—I felt sure I’d met her when I was small. The memory wouldn’t come clear, only the conviction that somewhere in my childhood’s blurred landscape, she’d been there. The obligation felt both ancient and immediate—the old contract between witness and testimony. She’d chosen me, or time had chosen me for her, to carry what remained of the 13th July , 1967, back into the world of the living.

How then could I refuse the dead their only request?

Yes, I will. I promised.

Thank you. And those were her last words.

Whereupon she got paler almost to the point I started to be struggling to distinguish her from the weakening amber light. Her form grew fainter, as if the telling itself were a key turning. The house listened once more, then let go.

Silence settled. In the mirror, only my own face looked back. Outside, the autumn wind stirred the leaves with nothing but its own voice. When I looked back the flat, the lamp that had burned for fifty-eight years went dark.

I stepped out carrying her story. Only then did I understand why she had chosen me: I, too, had my waiting hours—for a love that had left, for a life that would not arrive. Her warning was simple: waiting is not a life.

By morning, the old building was gone. The site stood empty—truly empty—for the first time since 1967. Perhaps that was her peace: not in death, not in the long vigil, but in being seen at last—remembered without the myth, carried forward without the neat bow of a moral.

I thought of the small things she’d wanted: the harbour at dusk, the steady tide, the children growing, the gray that comes honestly. I promised, out loud to no one, to choose one unglamorous act of living each day and to call it by its name.

She was weightless in every physical sense—a woman made of memory and air. Yet she’d been pinned to this place since that calender date by something heavier than any living body: the need to be known, to be remembered, to have someone say : yes, you were here and listened to.

Somewhere – if there is a somewhere – she should now feel lighter for having been told.

And somewhere closer, the part of me that kept a chair for what never arrived got up, switched on a new light, and began to write. Through the writing, the gray man at the present, the woman who never ages past 1967, and that child in a classroom sixty years ago became part of the same story—though which one of us was telling it, I could no longer say.

Written on 25 December 2025

(Epilogue to follow in the next post)